FIFA World Cup Final

Empire Stadium, Wembley, 30.07.1966

![]()

2-4 aet (1-1, 2-2)

Haller 12., Weber 90. / Hurst 17., 100., 120., Peters 78.

England: Banks – Cohen, J. Charlton, Moore (c), Wilson – Stiles, B. Charlton, Peters – Ball, Hunt, Hurst

Germany: Tilkowski – Höttges, W. Schulz, W. Weber, Schnellinger – Beckenbauer, Overath – Haller, Seeler (c), Held, Emmerich

Colours: Germany – white shirts, black shorts, white socks; England – red shirts, white shorts, red socks

Referee: Gottfried Dienst (Switzerland)

Assistants: Tofik Bakhramov (Soviet Union), Dr. Karol Galba (Czechoslovakia)

Attendance: 98,000

Match Programme Details

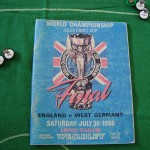

The commemorative match programme for the 1966 FIFA World Cup Final at Wembley’s Empire Stadium was a hefty sixty-four pages, and was sold for 2/6 – that’s two shillings and sixpence, half a crown, or – when converted into decimal currency – twelve and a half pence. The simple yet striking cover design featured the famous Jules Rimet Trophy in front of the official tournament logo.

The programme contained a welcome message from FA Chairman J. H. W. Mears, who sadly died during the tournament; it was followed by a comprehensive review of the competition, with complete team lineups, statistics and images from all of the previous rounds.

Aspect: Portrait

Dimensions: 218 x 170 mm

Numbered Pages: 64

Language(s): English

Match Report

Having not played each other for nine years between 1956 and 1965, the final of the 1966 FIFA World Cup saw England and Germany meet each other for the the third time in just over a year. With the two previous matches having been friendlies with nothing at stake, the Mannschaft’s third visit to Wembley was the first competitive encounter between the two sides.

Both sides could be said to have been lucky in making the final – England had looked distinctly unimpressive in earning a 0-0 draw with Uruguay and patchy in their victories over Mexico and France; Germany meanwhile had kicked off in fine fashion with a 5-0 walloping of Switzerland, but had looked far more pedestrian in their following games Argentina and Spain. They could only secure a goalless draw against a ten-man Argentinian side, and clearly benefited from having the extra man to come from a goal down against the Spaniards.

Interestingly, the quarter-finals saw England play Argentina and Germany take on Uruguay, and both teams were again to benefit from luck and controversial refereeing. Argentina’s skipper Antonio Rattín found himself unable to cope with England’s rough tactics and the referee not being able to understand him, and after having the better of their game against Germany Uruguay’s decision to resort to physical means resulted in their finishing with nine men. England won their game 1-0, while Germany went on to record what was in truth a rather flattering 4-0 scoreline. In what had to have been a strange coincidence, the referee for the England-Argentina game was German Rudolf Kreitlein, while the man who took charge of the Germany-Uruguay match was one Jim Finney – an Englishman.

The semi-finals saw Germany and England recording 2-1 wins over the Soviet Union and Portugal respectively, but even then there was a whiff of controversy. Germany once again appeared to benefit from having the opposition reduced to ten men – though not before they had taken the lead and proved to be the better side. England however were in the middle of a controversy that would never happen today. Originally scheduled to play their semi-final at Everton’s Goodison Park, they somehow were able to reschedule the fixture to Wembley, meaning that they would play on familiar turf (they didn’t play on any other ground during the entire tournament) in front of a crowd of nigh on one-hundred thousand.

The German team that took the field in the World Cup Final was makedly different from the eleven that had been selected for the friendly in February; The twenty-year old Franz Beckenbauer was no longer a promising youngster but a true star in the making, the defence was bolstered by the return of Karl-Heinz Schnellinger, and on-form striker Herbert Haller was available for selection. Perhaps the most crucial man in the line up however was skipper and talisman Uwe Seeler, who had against all odds overcome a potentially career-ending achilles tendon injury to make the squad.

I what was to turn into a dramatic final, the first goal came early. With some twelve minutes gone, the England defence made a hash of dealing with a hopeful Schnelliger cross, with Ray Wilson helpfully laying the ball on for Haller who stroked the ball into the net. With both Gordon and Banks and the defenders standing flat-footed and looking for others to deal with the danger, the ball hit the back of the net when it should never have got close to its intended target.

Germany had been bossing much of the play, and having taken the lead looked set to build on their advantage, but all of the good early work was undone not even five minutes later following a sharp piece of tactical awareness by England skipper Bobby Moore. After being fouled by Wolfgang Overath, Moore just got on with the game and ambled into what was acres of free space just inside the German half. How one interprets what happens next depends on one’s approach to the game – one the one hand Moore delivered a pin-point long ball into the box, on the other he hoofed the ball upfield in that typically English fashion. Either way, Hurst was there to meet it to level the scores.

In a game that belied the form of both teams coming into the final, the play flowed from end to end. While Germany were playing along the ground, England were with almost every move forward going aerial. Banks pulled off a fantastic double save from first Overath and then Lothar Emmerich, and then Tilkowski produced a string of fine parries of his own to keep the scores level at the half-time break.

This ebb and flow continued into the second half, with both goalkeepers doing enough to keep the scores at 1-1. However with twelve minutes left Tilkowski was left helpless as Horst-Dieter Höttges’ botched attempt to clear a scuffed Geoff Hurst shot placed a chance on a plate for Martin Peters, who couldn’t miss. The last ten minutes were frenetic: at one end England were trying to kill off the game, while at the other Helmut Schön’s side were desperately throwing men forward to take it into extra time.

In what was clearly their final throw of the dice, Germany threw everybody forward for an Emmerich free kick with mere seconds to go on the clock. Once again the England defence failed to clear the danger, with the ball falling to Siggi Held whose cross was deflected into the path of the twenty-two year old 1. FC Köln defender Wolfgang Weber. With Banks unable to make his ground, Weber slid in to prod the ball home. It was Weber’s first goal for the Mannschaft, and he was to score only one more in an international career that spanned some ten years and fifty-three matches.

Nine minutes into the first period of extra time, what turned out to be one of the most talked-about moments in international football happened. Following a cross from winger Alan Ball, Hurst spun on a sixpence and smashed the ball against the inside of the crossbar – which is where the story takes different paths. It has never been proven for sure that the ball was over the line – as it has to be for a goal to be awarded – but after a brief consultation in sign language between Swiss referee Gottfried Dienst and Soviet linesman Tofik Bakhramov (from that point on known as simply “the Russian linesman” even though he hailed from Azerbaijan), the players were directed back to the centre circle.

Clearly deflated at conceding the unlucky third goal, the German team no longer seemed to have the same coolness on the ball. Despite having to chase the game they made little headway, and the momentum swung clearly towards the home side who pressed for a fourth. In the dying seconds, Moore delivered a defence-splitting ball to Hurst, who buried his shot past the helpless Hans Tilkowski in the German goal – eliciting what the famous “they think it’s all over… It is now!” from commentator Kenneth Wolstenholme. 4-2 to England, and the first and so far only World Cup Final hattrick to Hurst. Technically, the goal should not have been allowed given that spectators had started running onto the field of play – not that it made much of a difference anyway, given that the damage had already been done some twenty minutes earlier by Bachramov.

Despite video analysis being used by both sides to either prove or disprove the legality of Hurst’s second goal – or “goal”, the fact remains that we will never know for certain if it actually crossed the line. If I were to be honest having seen all of the available evidence, I don’t think that it did. From that point on, any shot that came down off the inside of the crossbar was known in Germany as a Wembley-Tor, and in an interesting quirk of fate the very same thing happened during the second phase encounter between the two sides in the 2010 World Cup in South Africa – though with Germany being the beneficiaries of what was in this case an obviously poor decision from the officials.

Out of the eleven German squad members that played in the final in 1966, only one man – ‘keeper Hans Tilkowski – was over thirty. Even then, Tilkowski had celebrated his thirtieth birthday only eighteen days before the final itself. This young squad were to form the nucleus of Helmut Schön’s great German team – one that would dominate the European and World game for much of the following decade.

Note that I have not included a clip of the oft-repeated Kenneth Wolstenholme “They think it’s all over… It is now!” – I for one have seen it far too many times!

England’s rather fortuitous 4-2 victory also proved to be their last victory in their long unbeaten run against Germany; when the teams were to next meet in a Hannover friendly two years later, Germany would record their first victory – and with it end a desperate series that had seen them lose ten out of twelve games. (Or seven out of eight if one were to ignore the amateur period recognised by the DFB but not by the FA).

The victory in 1966 is seen in England as the country’s shining jewel in what has otherwise been a sea of listless tournament campaigns – every time an international tournament comes around the media affectation with 1966 kicks in – but one really has to wonder whether England would have even reached the final had they not been playing at home. As well as the controversial Wembley-Tor in the final itself, one can only wonder at how officials were able to change the venue for the semi-final against Portugal – not even Italy in 1934 with the meddling Benito Mussolini at the helm had managed to pull that sort of coup off. Might it have had anything to do with Sir Stanley Rous being President of FIFA? Who knows.

Even more controversial perhaps was the first-round elimination of the pre-tournament favourites Brazil, whose team had been hacked off the park by both Hungary and Portugal. These horror shows had seen Pelé in particular being brutally targeted by a battery of opposition defenders, but not one Hungarian nor Portuguese was shown to an early bath. One can of course consult any available record book or online resource to check on the nationality of the officials in both of these matches.

Had of course these tricks been conjured up by the Germans, the whole world would have been made to know about it – no doubt complete with an image of Franz Beckenbauer wearing an ill-fitting Pickelhaube.

England’s victory in the 1966 World Cup Final was to signal the beginning of what would be a thirty-four year drought against Germany in competitive fixtures; as far as matches that mattered were concerned, the Nationalmannschaft would remain the more dominant of the two sides until their meeting in the 2000 European Championship finals. While German football left the 1966 defeat behind and moved forward into the 1970s, their English counterparts simply chose to wallow in their victorious haze and rest on their laurels; one could even argue that nothing much has really changed.

Cumulative Record

Home: played 7, won 0, drawn 2, lost 5. Goals for 10, goals against 23.

Away: played 5, won 0, drawn 0, lost 5. Goals for 3, goals against 20.

Overall: played 12, won 0, drawn 2, lost 10. Goals for 13, goals against 43.

Competitive: played 1, won 0, drawn 0, lost 1. Goals for 2, goals against 4.